Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. New York: Random House, 1970.

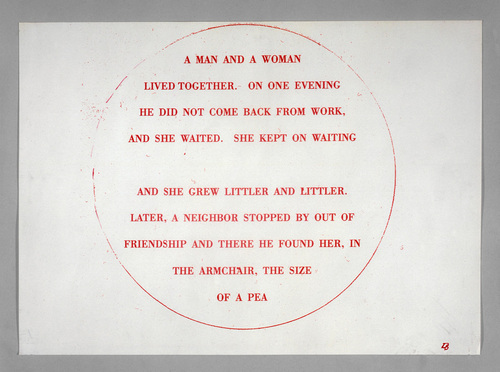

Reading Foucault be like...

Michel Foucault’s the Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences, discusses the breaking down of things (history, knowledge, man) into a certain order. In unpacking this ‘order’ Foucault is able to point out a series of assumptions that make up the orders (systems) through which we navigate our lives. Using a archeological methodology to analyze a series of historical epistemes, The Order of Things, seems ultimately about turning a dialectical eye to the systems through which knowledge is constucted and performed.

Any task to summerize the variety of thoughts, concepts, and explorations of this two part book would be futile. A summary would merely scratch the surface of the breadth of this book, and more to the point, I’m not sure I really understood it all. Instead, this blog post will focus on bringing forth and defining key terms that foucault introduces in this book, as well as a brief analysis of his methodology, intentions, and general conclusion.

Foucault describes the intervention of The Order of Things eloquently: “An inquiry whose aim is to rediscover on what basis knowledge and theory became possible; within what space of order knowledge was constituted; on the basis of what historical a priori, and in the element of what positivity, ideas could appear, sciences be established, experience be reflected in philosophies, rationalities be formed, only, perhaps, to dissolve and vanish soon afterwards (Foucault, xxii). In other word, Foucault seeks to analyze make visible the order of things; order being defined as the unconcious, normalize way things are structured or arranged, and ‘things’ being history, knowledge, man, or what Foucault calls the human sciences.

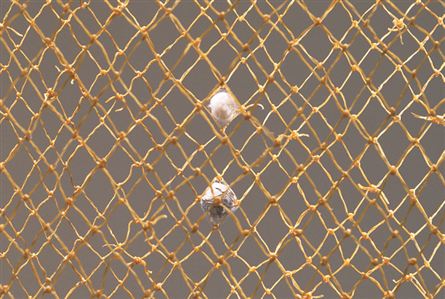

“order: “at one and the same time, that which is given in things as their inner law, the hidden network that determines the way they confront once another, and also that which has no existence except in the gird created by a glance, an examination, a language; and it is only in the blank spaces of this grid that order manifests itself in depth as though already there, waiting in silence for the moment of its expression (Foucault, xx). ”

Foucault goes about this analysis through an archeological approach. This approach differs from others methods of analyzing history and knowledge, because it seeks not simple to define something, but discover, in a genealogical sense, where it came from; what brought it into being. Archeological thought takes stock of a thing’s own context and time, and must ““must examine each event in terms of its own evident arrangement” (218). Yet is is ultimately interested in structures and orders that brought something into existance; ideologies upon which something is foudned. “The archaeological level of investigation is the level of thinking in a project which is concerned with what made something possible (31).

In thinking about the order of things archeologically, foucault brings in the word Episteme. This is the discovery of archeological thought; the order of things relates to its historical episteme. “In any given culture and at any given moment, there is always only one episteme that defines the conditions of possibility of all knowledge, whether expressed in a theory or silently invested in a practice” (168).

The episteme is what constitues the majority of the book.

pre-Classical period was structured on the episteme of resemblance.

- Naming/words: “it gives us a finger to point with, in other words, to pass surreptitiously from the space where one speaks to the space where one looks; in other words, to fold one over the other as though they were equivalents.” (10)

- signatures

- Language

“Classical” period was around the episteme of representation

- The whole Classical system of order, the whole of that great taxinomia that makes it possible to know things by means of the system of their identities, is unfolded within the space that is opened up inside representation when representation represents itself, that area where being and the Same reside. Language is simply the representation of words; nature is simply the representation of beings; need is simply the representation of needs. The end of Classical though – and of the episteme that made general grammar, natural history, and the science of wealth possible – will coincide with the decline of representation, or rather with the emancipation of language, of the living being, and of need, with regard to representation. 209

- Grammar/ Natural History/Analysis of Wealth

- the “Modern” period (the 19th century to about the 1950s), in which deep, dynamic historical explanations became important

- Thus, Philology, biology, and political economy were established, not in the places formerly occupied by general grammar, natural history and the analysis of wealth, but in an area where those forms of knowledge did not exist, in the space they left blank, in the deep gaps that separated their broad theoretical segments and that were filled with the murmur of the ontological continuum. The object of knowledge in the nineteenth century is formed in the very place where the Classical plenitude of being has fallen silent. 207

- Sade’s characters correspond to him at the other end of the Classical age, at the moment of its decline. It is no longer the ironic triumph of representation over resemblance; it is the obscure and repeated violence of desire beating at the limits of representation (210)

- to classify… will no longer mean to refer the visible back to itself, while allotting one of its elements the task of representing others; it will mean, in a movement that makes analysis pivot on its axis, to relate the visible to the invisible, to its deeper cause, as it were, then to rise upwards once more from that hidden architecture towards the more obvious signs displayed on the surface of bodies (Foucault, 229). In other words, “organic structure intervenes between the articulating structures and the designating characters – creating between them a profound, interior, and essential space (Foucault, 231)” and thus, “the very being of that which is represented is now going to fall outside representation itself (Foucault, 240).”

- A rupture in language: “At the moment when language, as spoken an scattered words, becomes an object of knowledge, we see it reappearing in a strictly opposite modality: a silent, cautious deposition of the word upon the whiteness of a piece of paper, where it can possess neither sound nor interlocutor, where it has nothing to say but itself, nothing to do but shine in the brightness of its being.” (300)

- No doubt, on the level of appearances, modernity begins when the human being begins to exist within his organism, inside the shell of his head, inside the armature of his limbs, and in the whole structure of his physiology; when he begins to exist at the centre of a labour by whose principles he is governed and whose product eludes him; when he lodges his thought in the folds of a language so much older than himself that he cannot master its significations, even though they have been called back to life by the insistence of his words. But more fundamentally, our culture crossed the threshold beyond which we recognize our modernity when finitude was conceived in an interminable cross-reference with itself. Though it is true, at the level of the various branches of knowledge, that finitude is always designated on the basis of man as concrete being and on the basis of the empirical forms that can be assigned to his existence, nevertheless, at the archaeological level, which reveals the general, historical a priori of each of those branches of knowledge, modern man – that man assignable to his corporeal, labouring, and speaking existence – is possible only as a figuration of finitude. Modern culture can conceive of man because it conceives of the finite on the basis of itself. Foucault, 318

- The rupture in language that sundered apart the thing and the word, produced a gap between “man and himself,” as he is now occupied by trying to think that gap, to think the unthought, his own otherness to himself and the otherness of the Other. thus, “Modern thought has never, in fact, been able to propose a morality. But the reason for this is not because it is pure speculation; on the contrary, modern thought, from its inception and in its very density, is a certain mode of action (Foucault, 328).”

MODERN EPSITEME

“A. Order: historical organic structures related by analogy of function

B. Signs: failure of representation

C. Language: impure medium; literature as showing being of language

D. Knowledge: fragmentation into 3 realms: formal; empirical; philosophical ”

Finally in the final sections of part two, after introducing some thinkers and figures that aided the epitemological shift into the modern era, Foucault turns to the human sciences and discusses man biologically, ecoonomically and philosophically. Now, I had trouble with this section, so I will turn to a summary I found online, by John Protevi, that I think is particularly useful.

““The key to the human sciences is their breaking the philosophical link of representation and consciousness (361). They do so, however, w/o escaping “the law of representation.” They bring unconscious structures to representation: they explain how life, labor, language are unconsciously represented by psychological, social, and cultural man. They explain how function, conflict and meaning are structured by norm, rule, and system so that man represents to himself the forces that determine him as object. The human sciences “treat as object what is in fact their condition of possibility” in a “quasi-transcendental unveiling” (364). But this success is that of knowledge, not that of science (366); they are in the vicinity of the sciences, borrowing their models from them, but their epistemic position forbids them that title. But this is not a negativity; the human sciences have their own positivity. ”

He closes Part two by discussing the counter-sciences: psychoanalysis, ethnology (social anthropology) and linguistics.

Ultimately, Foucault’s goals seem to be in creating a Archeology of Knowledge (the title of his next book). He’s curious in how things evolve along a path of thinkers, and epistemes; nothing is for granted, nothing is given, and yet defining orginins is a stragely circular business. By this I mean, not only is there at times a chicken and egg aspect to some of Foucault’s analysis, but also that to explore the Modern Episteme, he must start with the Classical one. And to address the classical Episteme, he must look to pre-classical thought. History starts and stops where and when the researcher does, they say. Regradless, Foucault’s exploration brings some complex thoughts together with culture, to discuss origins and their difficulty to in down:

““Generally speaking, what does it mean, no longer being able to think a certain thought? or to introduce a new thought. Discontinuity – the fact that within the space of a few years a culture sometimes ceases to think as it had been thinking up till then and beings to think other things in a new way – probably begins with an erosion from outside, form that space which is, for thought, on the other side, but in which it has never ceased to think from the very beginning. Ultimately, the problem that presents itself is that of the relations between thought and culture; how is it that thought has a place in the space of the world, that it has its origin there, and that it never ceases, in this place or that, to being anew? (50)”